In 2000, there were two trailers for the movie Cast Away that were released, one of which I’ve linked here. In it  you learn the entire plot of the film: a man gets on a plane, the plane crashes, the man is stranded on an island long enough to sport an impressive tan and facial hair, and he eventually makes it home after friends and loved ones have had a funeral for him and moved on as best they could.

you learn the entire plot of the film: a man gets on a plane, the plane crashes, the man is stranded on an island long enough to sport an impressive tan and facial hair, and he eventually makes it home after friends and loved ones have had a funeral for him and moved on as best they could.

After watching the trailer, I moved on, too. I had no need to see the film because the trailer was a sufficient SparkNotes-like version of the actual movie. But that’s not what movie trailers are supposed to do. They’re supposed to give you just enough information to make you want to see the movie. If the Cast Away trailer wrapped up after the first clip of Tom Hanks on a stranded island, I might have been all “oh-my-gosh-does-he-survive-and-make-it-back-to-Helen-Hunt?” about it.

Essays have their own trailers: introductions. An essay’s introduction should grab the reader’s attention, introduce some of the key elements of the essay, but not give away the entire argument so that there’s no need to keep reading. Most students want to know the secret for how to write a paper. The truth is that good papers are made up of many components, each with a specific purpose in driving your reader onward. With this in mind, here are some strategies that we executive function coaches teach for writing a successful introduction to a paper that is "movie trailer-like."

Write the introduction last.

If you son or daughter stares blankly at the page (or screen), feeling anguished about how to start writing a paper, then this is the most valuable advice you can give them. It’s not possible to properly introduce a paper when you don’t really know where the paper’s going to go. If the Cast Away trailer was made first, and then the directors decided to kill Tom Hanks’ character in a nasty but action-packed duel with a shark, the trailer would be misleading, and thus a poor intro to the movie. Have your child write just their thesis statement at the top so they don’t feel like there’s a lot of emptiness staring back at them. The introduction can be written and inserted later.

Think from your audience's point of view.

This is easier to show, rather than tell. These are two opening sentences from my students this spring:

A: While reading Daniel Gilbert's article, “Reporting Live from Tomorrow”, it made me really question what makes people happy.

B: What would you do if you had a million dollars? Your answer should be: give $900,000 away. That will make you the happiest.

Both students read Gilbert’s article, and both students wound up writing about the relationship between money and happiness. But when I showed these samples to 30 students, all of them said they’d only want to read “B.”

Here’s how “B” thinks about the audience: it poses a question to get the reader thinking, it gives an answer that surprises the reader which makes them want to read more, and orients the reader to the topic of the essay (money and happiness). Invite your son or daughter to think from their audience's perspective. What kind of introduction would be enticing to them? What kind of question would they find interesting to ponder that’s related to their topic?

Use Geometry in English class. Seriously.

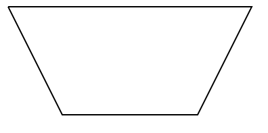

Think about an upside down trapezoid:

See how it starts wide at the top and narrows a bit towards the bottom? That’s what your introduction should do. Start broad -- a critical thinking question, a famous quote, a brief anecdote, or surprising statistic -- and then maneuver your way to your position or thesis statement. This might mean introducing the book you’ll be using to explore your ideas, giving the reader some context about the topic, or even defining key terms. Essentially you’re funneling your reader into the essay slowly, just like this trapezoid brings readers from a wide point to a focused thesis.

Each part of your paper deserves individual attention because each part has its own purpose. By using these 3 tips, you can write a great, "movie trailer-like" introduction that will make your reader hang on until the closing credits.

Executive Function coaches often work with students on writing assignments. Do you know a student who wants to learn how to write a paper, or learn organization or time management skills? Click below for a free phone consultation.

photo credit: Student - Studying via photopin (license)

Brittany Wadbrook is a college instructor, certified writing tutor, and senior executive function coach at Beyond BookSmart. She began her career in education at Quinnipiac University earning a bachelor of Arts in English and Masters degree in Secondary Education. While at Quinnipiac, she became a certified Master Level Writing Tutor by the College Reading and Learning Association and spent three years working for the University's Learning Center. Feeling motivated to expand her pedagogical skill set, Brittany pursued a second Masters degree in Composition and Rhetoric at the University of Massachusetts Boston. After graduating, she became a full-time lecturer at UMass where she currently teaches first-year composition to a diverse classroom culture including English Language Learners and nontraditional students from a variety of academic backgrounds. Brittany's experience with adult learners, diverse cultures, and a range of learning abilities has enabled her to become a flexible educator who is sensitive to individual learning needs and intrinsically invested in their educational success.