Visiting a professor during office hours in college can be a daunting task, especially for  freshmen. Students wonder if they should just stop by to introduce themselves or if they must prepare specific questions. Anxiety might take over, with students fearing they won’t sound smart enough or seem like “college material.” Students often think: “What if I make things worse by meeting with my professor?” and “What if I totally blank out and embarrass myself?” All of these concerns are valid, but avoidance tends just to perpetuate the vicious cycle of fear, and students lose the valuable opportunity of one-on-one time with their professors.

freshmen. Students wonder if they should just stop by to introduce themselves or if they must prepare specific questions. Anxiety might take over, with students fearing they won’t sound smart enough or seem like “college material.” Students often think: “What if I make things worse by meeting with my professor?” and “What if I totally blank out and embarrass myself?” All of these concerns are valid, but avoidance tends just to perpetuate the vicious cycle of fear, and students lose the valuable opportunity of one-on-one time with their professors.

As both an Executive Function coach and a college instructor, I am in a unique position to guide my college-level clients as they develop self-advocacy skills. By drawing on my dual background as a coach and a college faculty member, I help students prepare for these often-feared meetings and manage their expectations by offering my own perspectives. For instance, I share with clients something my colleagues and I often discuss among ourselves: the disappointment we feel when students wait too long to ask for help! Professors want students to improve and they will often reach out to struggling students to offer assistance. Nevertheless, students must direct the process. Most college-level clients I have worked with are aware that improvement takes time. Yet, anxiety or fear leads individuals to defer the meetings that could lead to growth. As a coach, it is part of my job to help students see that they are caught in the vicious cycle of task avoidance and to urge them toward gradual change. By going to office hours and asking a few questions for clarification, a student can be on the road to improving a paper, performing better on exams, or designing a stronger in-class presentation. Once the first meeting is over, it is usually easier to return. At this point, visiting office hours can become a positive habit.

Tip #1: Scripts for meetings (and for yourself!)

During coaching sessions, I work with college-level clients to “script” out an approach for the meeting. An initial meeting with a professor may feel a little uncomfortable. That is why going in with a plan, or roadmap, can be helpful. To counter negative thoughts and stay on topic, we practice “self-talk.” For example, students might generate two or three claims that reflect their positive traits such as “I complete all of the readings, so I already know a lot of information,” or “I want to improve, so I should take advantage of the opportunity to ask my professor these specific questions I’ve prepared.” These claims are a starting point for conversation, and they can be returned to if the student’s confidence starts to waver in the middle of a meeting.

Tip #2: Keep the focus on building skills, not earning points

Another piece of advice I offer students is to ask their professors what they can do to improve in the course, as opposed to trying to negotiate for better grades. Often, students are worried about the effect poor grades have on their academic future and they approach meetings with professors in defensive—and occasionally even hostile—ways. A teacher well-trained in pedagogical methods will know how to redirect the conversation, but the student’s attitude can leave a bad impression. By mapping out a plan for the meeting and identifying the main goal or outcome, students can avoid an unpleasant dialogue and engage productively in figuring out where to go next in the course. An opening question might look like this: “I see from your comments on my essay that my thesis summarized the novel instead of making a claim about it. Do you have some suggestions for how I can move from summary to argument?”

Tip #3: Start building self-advocacy skills before college

For students in high school or middle school, I recommend getting a head start at meeting one-on-one with teachers whenever possible. Before college, parents often step in on behalf of their children to discuss ways to support their academic growth. While the intentions of parents are good, they might be inadvertently depriving their children from gaining experience in self-advocacy. This lack of experience can leave students unprepared and more anxious when they arrive at college. To break this cycle, I suggest that parents and children sit down together to discuss successes and challenges in their classes. Then, they can come up with a plan for approaching a specific teacher. While parents may want to meet with teachers in person, I think it is important for the child to follow up one-on-one with the teacher to ask their own questions or voice their own concerns. Tools such as self-talk and scripts are useful to use with middle school and high school students as well.

Tip #4: Recognize the benefits of developing self-advocacy skills

Just like anything else, it takes practice to develop these skills of self-advocacy. Also, it might prove useful to think about the long-term effects of developing self-advocacy skills. The relationships college students build with their professors can serve as a guide for those they have in work settings and various professional contexts. I recommend looking at meetings with professors as part of every student’s preparation for entry to their professional lives, beyond the college context.

So, schedule that appointment with a teacher or professor (or just show up if they have walk-in office hours!). Break the vicious cycle of avoidance and start the cycle of growth. Not only might these meetings help improve your academic performance, but they can have a lasting impact on your ability to self-advocate effectively in other areas of your life.

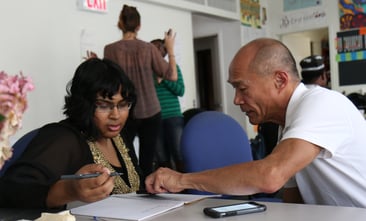

Photo above by Monica Melton on Unsplash

Elizabeth Porter wrote this piece at the end of the spring semester of 2018 when she was working full-time as a postdoctoral teaching fellow at Fordham University and part-time as an Executive Function coach at Beyond BookSmart. For the past decade, Elizabeth has worked in various university settings in both teaching and advising positions. In all of her roles, she prioritizes teaching self-advocacy skills so that students feel empowered to ask for help. She earned her Ph.D in Eighteenth-century British literature from Fordham University in August 2017

Elizabeth Porter wrote this piece at the end of the spring semester of 2018 when she was working full-time as a postdoctoral teaching fellow at Fordham University and part-time as an Executive Function coach at Beyond BookSmart. For the past decade, Elizabeth has worked in various university settings in both teaching and advising positions. In all of her roles, she prioritizes teaching self-advocacy skills so that students feel empowered to ask for help. She earned her Ph.D in Eighteenth-century British literature from Fordham University in August 2017

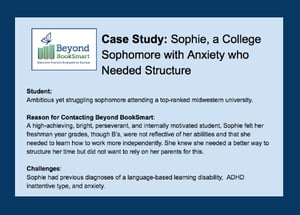

Find out how coaching helped Sophie, a college sophomore who learned that meeting with professors helped her to feel more confident and less "stuck" with her writing assignments.

Find out how coaching helped Sophie, a college sophomore who learned that meeting with professors helped her to feel more confident and less "stuck" with her writing assignments.